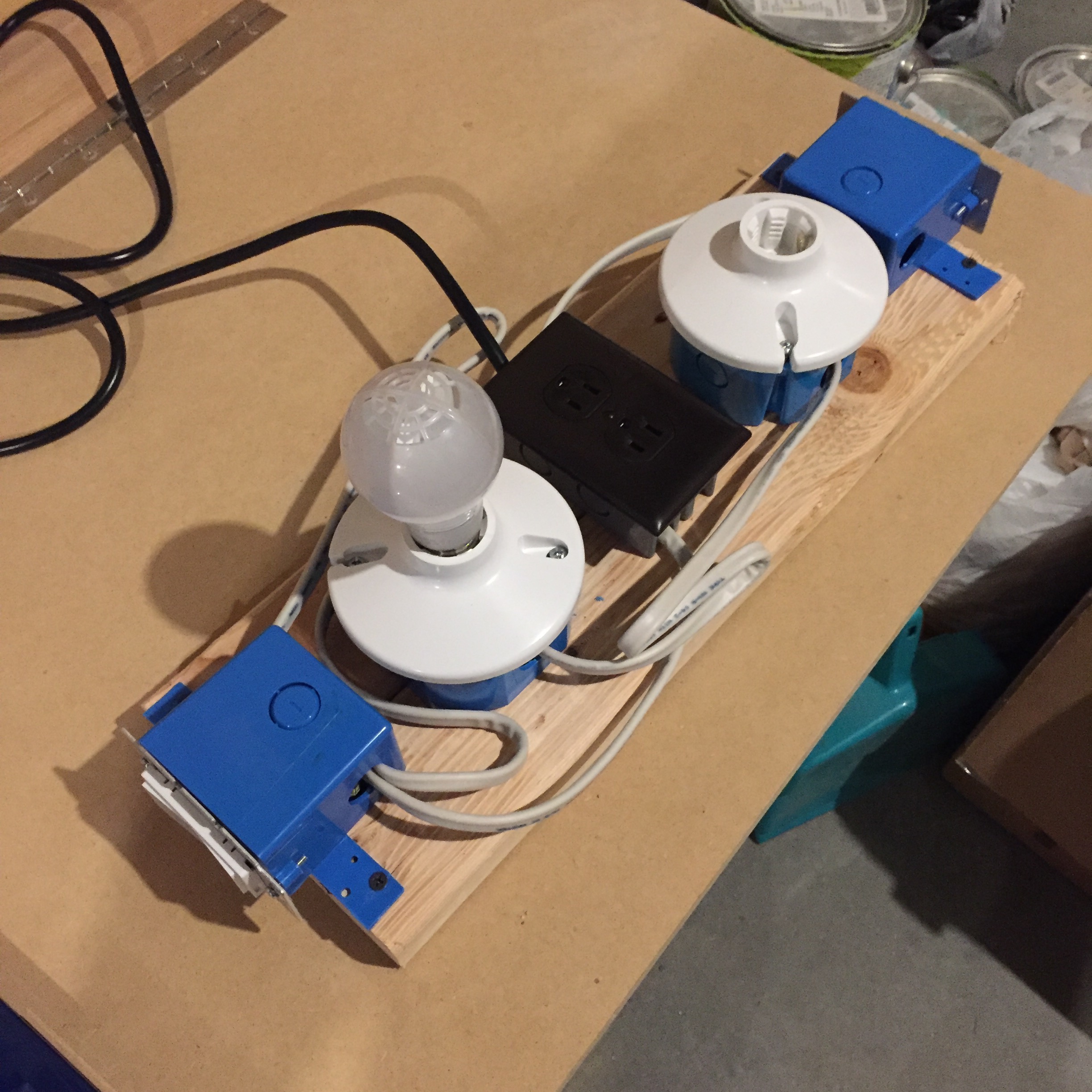

Z-Wave Project Board

When it comes to smart home or home automation doo-dads, some you put a battery in and stick on a shelf; some you plug into the wall wherever you want the thing. But yet others require you to open up a part of your house and dig around in its guts.

I wouldn’t dream of installing a smart water flow meter without testing it out first, and the same should go for a Z-Wave dimmer switch.

It can take a lot of work to get this class of devices installed. Even a simple switch requires some patience and elbow grease, and it almost certainly involves some new wiring, even if it’s just a new pigtail, because the smart switch requires a neutral where the old dumb switch you’re pulling out didn’t.

Even assuming that your home has a neutral available in every switch box, that’s just one less thing you have to worry about. You still have to use a volt meter or a multimeter to properly identify your line, load, and any traveller wires. Then you turn off your breaker (and the breaker for any adjacent switches in the same gang box – you don’t want to shock yourself on a switch you’re not even working on), do the old switcheroo and power everything back up.

What if it doesn’t work? How can you identify your own shoddy workmanship from a DOA product?

That’s why I put together this project board. It’s nothing fancy, just something I threw together from some parts I had laying around and a few cheapo components from the hardware store.

All strapped to a couple of scrap 2x4s:

- A dishwasher power cord wired into an outlet;

- Two keyless light fixtures;

- Two deep boxes.

- A few feet of Romex.

In its current configuration I have installed a GE Smart Dimmer Switch and a companion GE Add-On Switch for 3-way action. The load is the two keyless fixtures, one of which has a dimmable LED A19 bulb installed.

This setup allows me to:

- Make sure I understand how the equipment is wired up;

- Make sure the electronic equipment I just bought is in working order;

- Make sure the devices will pair to my SmartThings hub;

- Make sure the Device Type is appropriate for the expected behavior of the devices;

- Etc.

All this before I involve the actual wiring of my house, my ability to fish a neutral out of a tight space, etc., etc. It takes one more variable out of the equation if I should discover that something isn’t working right after the real installation – if it worked on the project board, the problem has a smaller solution domain.

Plus, I can easily re-wire the thing to simulate other installation use cases or demo/preview different devices, like this two-load module from Monoprice, for which the documentation is just inscrutable enough that I don’t want to install it until I understand how well it works.